The chatbot challenges

A while ago, my dad complained to me about the customer service of his energy company. "Normally," he told me, "you get to chat with this computer but if you force it into giving you the same answer over and over again, some real person will step in. But these days that doesn't happen anymore!"

In this case, my surprisingly tech-manipulative father had probably run into a combination of general labour shortage and peak demand for customer service in the energy sector. But in the near future the amount of human 'handlers' per chatbot will drop, as the chatbots are getting more and more sophisticated. Soon, it will be much less likely to speak to a real human if you contact customer service.

In fact, we might not only see remote customer service jobs disappear in the coming years, Internal support desks in companies will also see their work transformed. If you have a proper knowledge base, linking it with a program like ChatGPT can speed up internal communication and in addition, these programs can help structure any text you throw at them. I can see future knowledge workers sending their 'word vomit' to conversational machines , which then neatly edit and restructure it into a readable text.

This is despite the fact that ChatGPT and its brethren are dumb. One might marvel at ChatGPT's parlour tricks (write a sonnet on brewing an IPA while referencing postmodern philosophy) or get uncomfortable at the ease with which it integrates information (write an essay in which you explain the combined value of optogenetics and behavioural economics). But as with most machine cognition, the impressive feats are by virtue of scale, not underlying intelligence.

ChatGPT has processed more text than a human will ever read and it mixes and matches elements from this huge corpus to any utterance thrown at it. Because the corpus is huge and because the mixing and matching is advanced, the program behaves in a way that we would find intelligent, were a human to do it.

However, that's not the same as the machine being intelligent.

Now I can hear the preachers of the Singularity balk at this claim from a distance. 'Neurons are also dumb! It's scale that gives the human brain its power! How do you know humans are not just mixing and matching? You are just moving the goal-post for what counts as intelligent!'

All these points are valid and, as an aside, I believe humans indeed have a "stochastic parrot" mode of sorts – we call this rambling. Yet I think it's still justified to call humans smart and ChatGPT-like bots dumb. For that claim, much like an artificial intelligence researcher using neural networks, I draw on thinking done in the 1980s.

The Chinese room argument

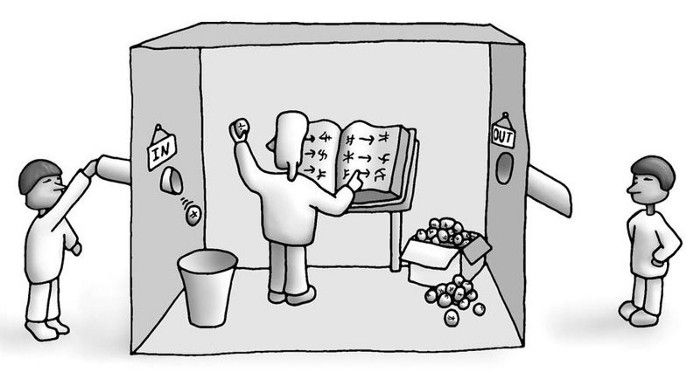

Imagine an operator who finds himself stuck in a room, where he receives written questions in Chinese, a language he cannot read or speak. The operator does have a manual available and this manual details complicated instructions on what to do with the sequences of Chinese characters, in such a way that he can generate an answer – in Chinese! – that makes sense to Chinese-speaking people.

The question now is: Does the operator understand Chinese?

For John Searle, who introduced this "Chinese Room Argument" in 1980, the answer was a clear no. Just having the procedural knowledge on how to create a sensible response is, he argued, not the same as understanding the questions and generating an answer that has meaning to you. In Searle's view, any machine that can hold up a conversation well enough to pass the famous Turing Test may not be understanding anything.

Not everybody was persuaded by the argumentation, however. Ned Block and other thinkers argued that if you interpret the metaphor carefully, the question should not be whether the operator understands Chinese, but whether the system of operator and manual understands Chinese. For a detailed discussion of the philosophical history of the argument, see here.

I'd go a step further than this so-called Systems Reply and would argue that the understanding of Chinese is also not just in the operator plus manual, but in an even larger system in which the manual is entangled with its creators. The manual is an artifact that represents understanding, but that understanding itself is in minds that are external to the Chinese Room. You might think I am being overly mystical here, but in fact I think understanding always need to be grounded in physical reality to make sense – the symbols in a manual lack this grounding, but the agents who created it presumably are actors in the world, for whom the symbols are meaningfully connected to reality.

This line of thinking can be transferred to ChatGPT. The program has been trained on a huge corpus of human-written text, full of lexical fragments that represent human understanding. It then acts on these representations left by human understanders, without understanding them itself. This is still a powerful approach: ChatGPT generates structured text because it has been trained on many texts structured by humans and similarly, it groups concepts together because it has been trained on texts in which humans do this. Through the sheer power of correlation, it can even pass Winograd schemas, tests originally designed to assess understanding:

The sports car passed the mail truck because it was going faster.

Which car was going faster?

The sports car passed the mail truck because it was going slower.

Which car was going slower?

However, because it does so via patterns in the training corpus, it is not difficult to create new schemas where it (but not humans) fail dramatically. Ultimately, even in the case of the solved schemas it's still the creators of the texts that imbued the corpus with meaning. These understanders remain outside of the room, while ChatGPT has to work with the patterns it extracted from the manual.

The challenges for education

Dumb machines are good enough to disrupt the economy and they are good enough to foil the attempts of educators to assess their students. ChatGPT might not understand anything, but its behaviour is much like that of a student who does understand something. That means that students who are somehow motivated to feign understanding can do so with ChatGPT or similar programs. And they do.

Can we avoid this by changing the specific assignments we use? There is no easy way to determine what ChatGPT can or cannot do in advance. As with all machine cognition, it will be good at some things that humans find hard and bad at some things we find easy. You'd expect tasks that depend on genuine understanding to be impossible for ChatGPT-like programs, but when does a task require genuine understanding? And what to do with those tasks that are useful for student growth but are also trivial for ChatGPT to pull off?

There might be no real way out for educators. We want learners to practice the things that machines can now also do, so we have to persuade these learners to put in the effort themselves. More than ever, it's important that we explain why writing is an important skill and why proper sourcing is important to academic work. While it is true that workplaces will soon feature large language model-assisted writing support, the cognitive benefits of learning how to structure and formulate thoughts are still worthwhile. It is the playing with ideas that helps learners gain understanding – the thing that still separates humans from machines – and writing is one of the playgrounds.

To keep ChatGPT-mediated plagiarism at bay, we might want to bring students back into the classrooms and monitor their learning and understanding more closely than before. That still leaves room for writing exercises, but perhaps graded written work needs to be created within examination halls again. I don't think we'd lose much that way – a timed writing exam might even be a relief for some students.

What I think we shouldn't do is bring ChatGPT into the classrooms ourselves. I am sure there are fun and even instructive applications out there, but it is an ethically dubious technology. Even if its externalities don't bother you, it is worth considering that ChatGPT is essentially a plagiarism engine – it took content from the internet, chewed on it for a while and is now regurgitating the mash-up for a fee. I am not sure how we can argue against plagiarism if we use a tool like that ourselves.

But mostly educators should keep their eyes on the prize. The new conversational machines are still just tools, bags of tricks that can mesmerize and that will certainly find commercial applications, but that are limited in their potential. We will still need reflective humans who understand the world around them in the times that are ahead - and it remains up to educators to train them.

Member discussion