From critical thinking to critical talking

Today’s critical thinking education wants the improve the reflective reasoning of individual learners. This makes sense: productive workplaces, healthy democracies and innovative research centres can all benefit from people who can reason deeply, all by themselves. Still, there are good reasons to not just focus on training critical individuals, but to improve the critical capacities of groups, too. Here are five reasons to teach “critical talking” and foster critical communities.

Reasoning is a social process

Critical thinking is a form of reasoning. And since evidence from the cognitive sciences suggests that reasoning is a social process, it makes sense to look at critical thinking as a social process, too (Mercier, 2016). Humans are natural reasoners, who clarify their own thinking and learn about different perspectives by talking to others. And while such natural conversations are not always critical — as shown by myside bias and groupthink — this could just be a matter of training. For example, the Socratic method add a critical structure to natural, dialogue-based reasoning.

Everyone has a role in critical talking

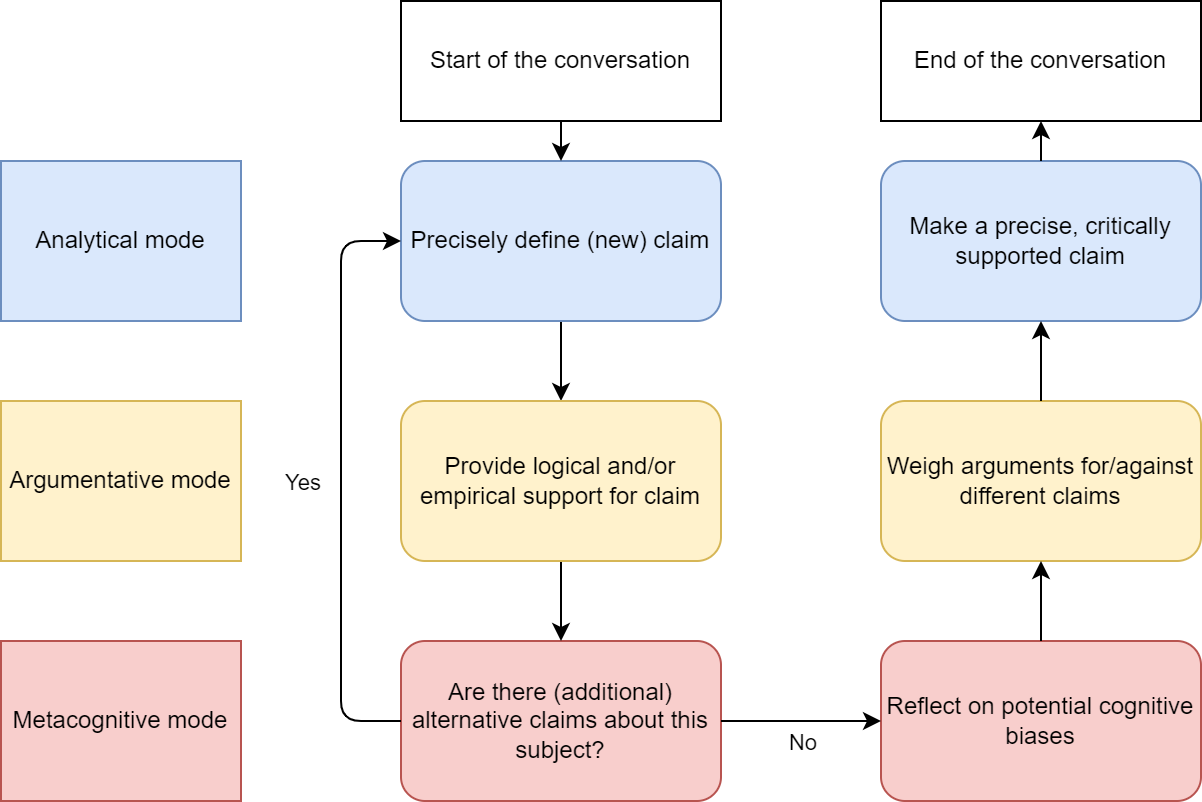

As this blog keeps repeating, critical thinking is container concept for a process. It touches on many different skills that act on existing world knowledge. Perhaps all these skills can be taught or trained, but in practice different people have different cognitive styles. In critical conversations, there is a role for the analytical thinker, for the arguer and for the divergent thinker who sees new options or second-guesses someone's line of thinking. A critical conversation moves back and forward through three different cognitive modes. weaving a full deliberation in the process.

This way, many people can contribute to critical thinking at a group level. A diverse group of people, none of whom score very high on all aspects of critical thinking, could still do well an critical thinking tasks if they know how to engage in critical conversations. By doing so, they can combine their individual strengths.

No worker is an island

There is no doubt that a coder should be able to analyze and trouble-shoot code on her own. Similarly, data scientists and researchers should be able to think on their feet and solve problems as they arise in their day-to-day activities — that’s what makes them skilled labor. However, how often do people do their job entirely by themselves?

Perhaps more than ever, workers are embedded in networks and organizations, which gives them the opportunity to share insights and perspectives. If you train people to not just be solid reasoners by themselves, but also teach them to think critically with others, workers can collaborate to question assumptions and find novel solutions. By providing students with such critical social skills, their labor value increases.

Organizations need it

Even if every department of an organization is populated by deep, critical thinkers, it is still important for them to exchange ideas with each other. Only through such exchange can organizations change to become more productive or to adapt to a changing world. However, critical exchange does not come naturally in the face of power relations. In more or less hierarchical structures, critical questions can be considered threatening by those higher up the food chain.

Training people to think critically together will not completely dissolve the difficulties caused by power structures, but it helps. Bringing critical discussion methods into organizations ideally fosters critical communities, in which tough questions are a by-product of professional communication and not a showdown between a critical questioner and a socially threatened manager.

Democracies need it, too

In their ideal conception, democracies are political structures in which all citizens deliberate about collective decision-making. Those citizens may have different values, different preferences and different interests, but through argumentation and persuasion, such differences can be resolved peacefully.

In practice, though, democratic deliberation is a messy process. Personal cognitive biases, fueled by divisive rhetoric from politicians and social media accounts alike, have a tendency to distort our reasoning to the point that our beliefs make us susceptible to false claims. On top of this, opinions are cheaper than — and in practice often precede — deep analysis. The net consequence of these issues is that political discussions are barely intellectual processes: they consist of a few sides trying to find persuasive arguments that match their positions.

In times gone by, editorial boards, discussion moderators and interviewers could — at least in principle — attempt to steer such discussions into a productive direction. This world is gone now and has been replaced by non-moderated exchange. The skills that are needed to hold critical conversations could improve such exchange.

Critical dialogues

Education, work environments, organizations and even democracies can benefit from ‘critical talking skills’. These talking skills, by the way, are also listening skills: really hearing what others try to say and only then asking questions that further clarify their thinking. The structure of critical dialogues and the questions you can ask to analyse someone else’s reasoning can be taught and go a long a way towards strengthening criticality in groups.

References

Mercier, H. (2016). The Argumentative Theory: Predictions and Empirical Evidence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.07.001

Member discussion